Motorcycle Loop

24 February 2023

Algorithm and blues.

I’ve been thinking more and more about content recommendations. Specifically how those recommendations are developed and delivered. With the Supreme Court weighing the role of recommendation engines in radicalization, along with my recent daily use of the new Artifact app and my never-ending desire for a great music recommendation engine, the idea of “content” in “content recommendations” has been on my mind a lot lately.

There are plenty of more well-informed people writing about the Supreme Court. I’d recommend (I use that term knowingly) getting updates from NPR’s Nina Totenberg and analysis from Slate’s Slate Marc Joseph Stern and The New Yorker’s Kyle Chayka. What I want to talk about is how videos at the center of those cases ended up in front of the eyes of terrorists. To put it far too simply, our recommendation engines are broken.

One of the reasons I think this is because our current systems and algorithms rarely reward curiosity. Here are a couple of examples: Let’s say you want to know why the bar across the street just erupted in cheers. You look on Twitter, for instance, to see that the Golden State Warriors are playing, and scroll through a few Tweets to learn that they pulled out a win in the last seconds of a regular-season game. The recommendation engine has no idea what motivated your search. All it thinks now is, “MUST SEND MOAR BASKET BALLS!” [Please read that in the voice of Frankenstein’s monster.] But you don’t really like basketball. You were just curious, and found an answer to your question. But now your Twitter timeline is suddenly injected with NBA-related Tweets you have no desire to see. It’s misunderstood you and the limited number of signals it can read about you. There’s no way it knows that you’re five-foot, six and couldn’t sink even a layup even if your life depended on it. But let’s look at another example, shall we?

For people who follow the news closely, there is a lot of value in having a wide array of sources to get your updates. But if you’re using an app like the new Artifact, the narrowcasting can happen pretty fast. If you read a New York Times article, for instance, a lot more Times articles end up in your feed. The same happens for topics. If you read about a local break-in in your neighborhood, you run the risk of having your feed overtaken by crime reporting. It almost makes you reluctant to stay informed for fear that you’ll only get those types of stories over and over. It’s like telling your grandmother when you’re 7 that you like penguins, only to get penguin-related gifts from her for the rest of your life.

One last one, if you will. Say you have a gloriously broad set of music you like. And, occasionally, you explore bands you read about by looking them up on Spotify. So, you listen to an album you read about on Pitchfork, or wherever, and then, suddenly, your Daily Mix 4 is full of bands who think whistling and stomping and clapping are the-end-all, be-all of songwriting prowess. All because you wanted to try something new.

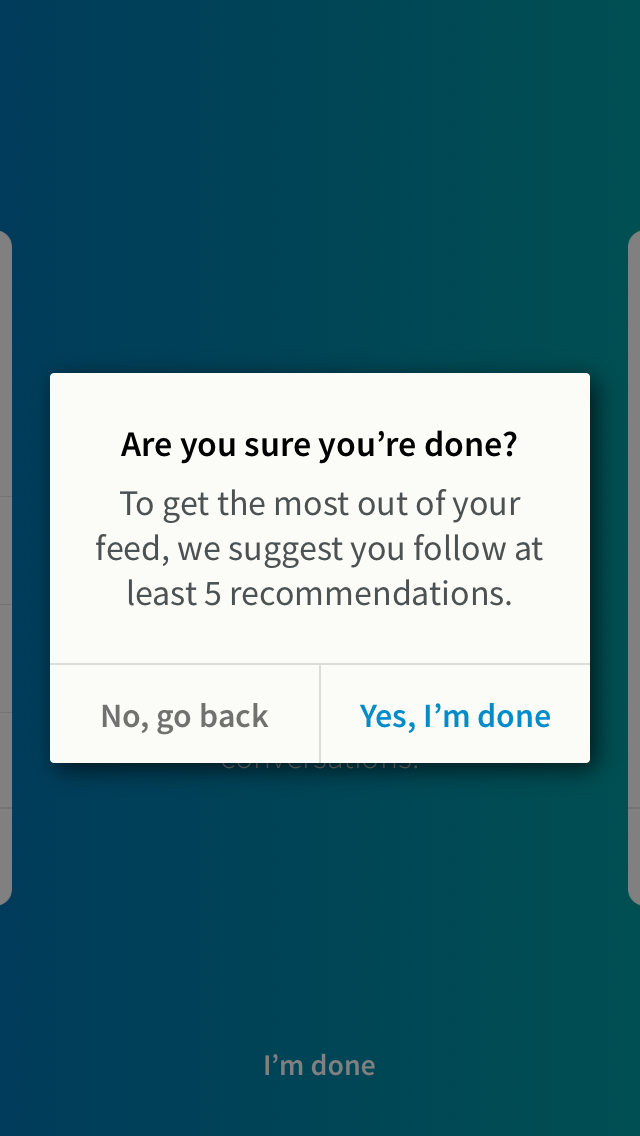

I guess what I’m saying is, we need more control. We should be able to explicitly indicate what we like and what we don’t. If we were better at providing that nuance, I’d trust these algorithms more to recommend things to me. And as we move away from cookies and personalization, and toward privacy and control, we might be able to get there. As long as corporations can profit from it, I assume.

See you tomorrow?