Curiously

Sketchy.

This post was a long time comin’. It’s not that I’ve been drafting it for ages (actually, I just hastily sat down and started smashing at keys) but more like these thoughts have been bouncing around in my head for ages and it’s time to write them down. And, just in case I get to ramblin’ and publish without editing (which is highly likely when I get in this kind of mood, using a lot of parentheticals), here’s the TL;DR: Hire people who can think, and they will learn the tools.

Now, the obvious conclusion you may be jumping to is, “Oh, great, another blog post about large language models and machine learning and artificial intelligence and I’m already too bored to even roll my eyes.” I get it. But this isn’t that. Well, it’s not not that. But I’ve also been thinking about the expectations that some hiring managers have around the expectations of what we should bring to a job. Let’s add some context first, shall we; have time for a little story?

For more than a year, I’ve been part of an amazing Design org, working on some thorny problems for a fin-tech client. We were set up in pods — not my favorite of classifications — tasked with integrating a point-of-sale technology into a payments behemoth. Thankfully, the Pod™ had an amazing mix of Designers and Researchers, so we were able to really dig into what our customers needed to ensure a friction-less (as much as possible) transition into a new, larger ecosystem. We talked to dozens of our customers. We held workshops. Did experience audits. Designing. Prototyping. Iterating. All so we could get at the most important problems to solve. And what sticks with me most through all of this is how often everything changed around us.

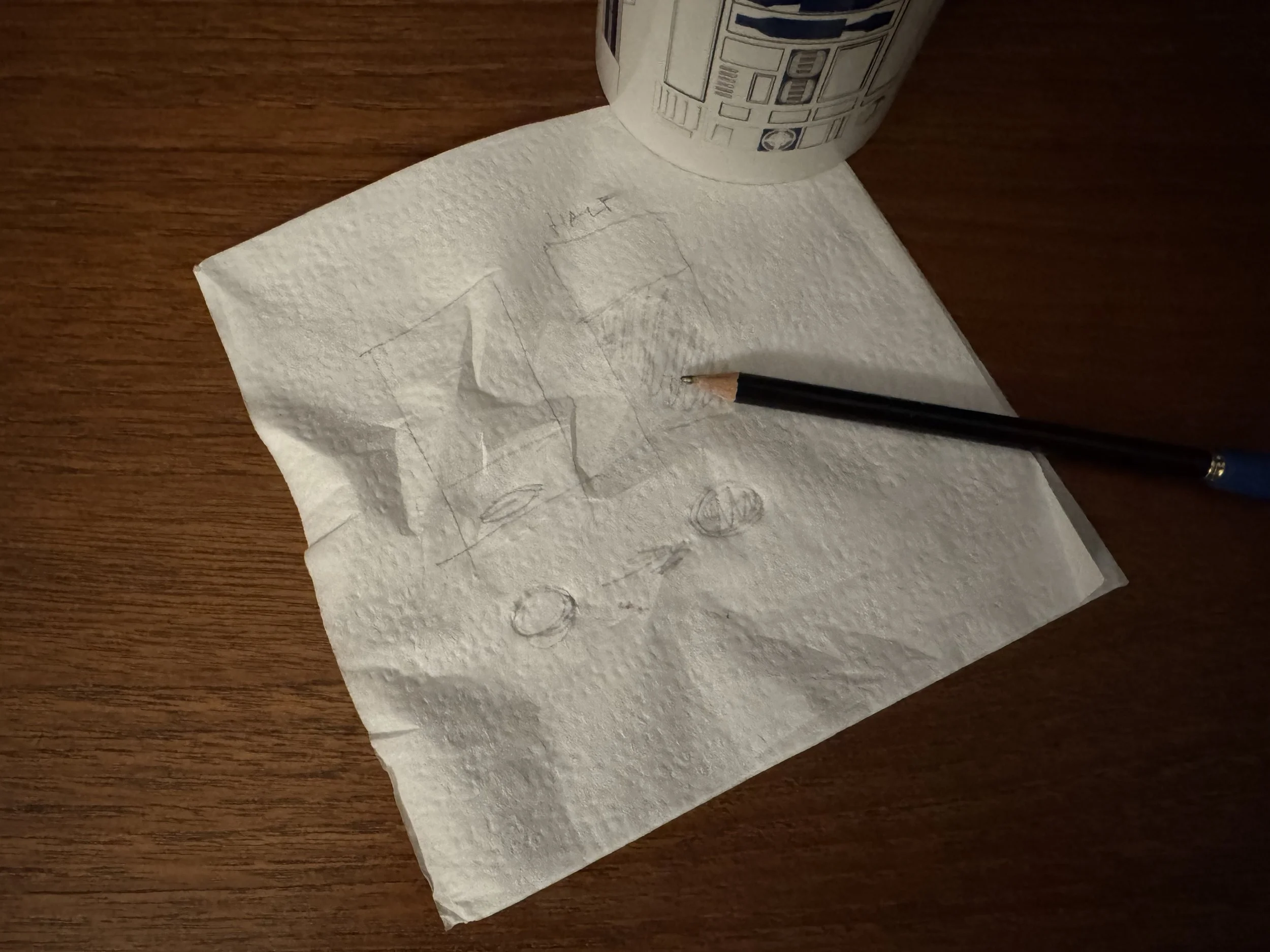

New tools? Check. New leadership? Check. New business goals? Check. And on and on. What was constant, however, was the team’s ability to think through any new problem and come up with at least a couple of ways to solve it. I chalk that up not to any of them being great at Figma file structures or creating the best Miro board, but to them having the kind of minds who could solve a problem by understanding people’s needs and telling a compelling story about how we could meet them. And they could do that with a pencil and a napkin.

For me, often writing is thinking. I need to sit down with myself for a bit to start crystalizing the swirl of fragmented ideas in my head. Just tapping them out like this helps me make connections and reveal an understanding I may not have had prior to my first letter hitting the proverbial page. But again, I could start that process with a pencil and a napkin.

The tools we use these days make our jobs easier. Most of the time. Ideally, that ease leads to increased productivity, which (hopefully) drives more solutions for our customers. But without the thinking, it doesn’t matter how many tools we know how to use. No bad idea gets better just because it’s pixel-perfect. In fact, the bad ideas needed to be tossed well before we even selected a design system component. Or created a design with Figma Make. Or prompted Replit. To co-opt the title of a very valuable book to me, thinking is designing. If we’re not hiring thinkers, we’re not solving problems.

Now, could I have prompted my way into this post? Probably. But I’m pretty sure to get to something which resonated with me, it would have taken much longer (and definitely a whole lot more potable water) than the over-caffeinated sweating out of the paragraphs you’ve just read. There isn’t a lot of magic to what I do. But it is work. And that work includes learning new ways to work. Whether that’s understanding some new design software, navigating corporate intranets, or figuring out how to collaborate with a new teammate. Curiosity will always be your most important hiring criteria.

From now on, I only want to be a part of teams where “work” means you are learning something new every day. Especially if what you are learning is about how to make your customers’ lives easier. I’m taking a break for a bit, but if your team is hiring exceptional thinkers, let me know. I know a few great ones who just became available.